What springs to mind if I ask you to define homelessness? A guy selling the Big Issue outside the station? A faceless shape in a sleeping bag, lying on some cardboard in a shop doorway?

What if I was to tell you that the legal definition of homelessness does not necessitate you not having a home? Under the law, even if someone has a roof over their heads, they can still be homeless. Put simply, they may not have the right to stay where they are or their home may be unsuitable. Homelessness is sneaky in its definition and potentially devastating in its effects; even if you have a roof over your head.

Research carried out for Shelter (Anderson and Thomson, 2005) found that young homeless people do not identify with the stereotypical notion of homelessness as sleeping on the streets; instead, they recognise that what they are going through, sleeping on a different person’s sofa every week, living out of a bag. This is the other, more hidden definition of homelessness. It may seem to be a ‘better’ version of homelessness, it may involve having access to shelter but it is no less catastrophic in its effects, particularly on mental health.

Being homeless is not defined by not having shelter

Prevalence of homelessness and mental illness in children and young people

Kate Hodgson and colleagues have undertaken a follow-up study, exploring the prevalence of psychiatric disorder and comorbidity among a UK sample of young people with experience of homelessness. Their aim was to examine the longitudinal relationship between psychiatric conditions and different types of health service use.

The mental health risks to young homeless people are well established, with particularly high rates of conduct disorder, PTSD, major depression and substance misuse reported. Poor physical health and high rates of personal injury are also common. It goes without saying that to be young and homeless is usually caused and compounded by circumstances which fundamentally affect how and whether individuals are willing and able to access primary care and other appropriate health services.

The researchers examined the relationship between specific forms of mental disorder and health, and mental health service use at follow-up.

Conduct disorder, PTSD, depression and drug use are all common in young homeless people

Methods

- Young people were recruited between January 2011-January 2012 via Llamau, a homelessness charity covering southern Wales

- In line with the UN definition of ‘youth’, participants were eligible if they were between 16-24 years of age

- A prospective, longitudinal design was used with 8-12 months between 2 interview-based assessments

- Contact was maintained via a newsletter, birthday cards and personal contact with a relative/friend

- Structured interviews included a full psychiatric assessment (MINI PLUS Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0) and questions about recent health service use (mental health, emergency room, general practitioner, hospital for physical problems, drug or alcohol services)

- A brief systematic review was conducted in parallel in order to examine the relationship between mental health service use among young homeless people

Key findings

- 121 young people with experiences of homelessness undertook an initial assessment. All were legally defined as being homeless

- 90 were traced at follow-up and re-interviewed (74.4% retention)

- There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of age, sex, ethnicity or sexuality

- The overall prevalence of any psychiatric disorders within the young homeless sample was very high at 87.8% for the current disorder (n=79)

- Over 70% of the sample (73.3%, n=66) met the criteria for two or more current psychiatric conditions

- Over half of the sample had visited their general practitioner (GP) in the previous 3 months (60%) while a high proportion had also accessed hospital services (42.2%) in the past 3 months

- Approximately 10% had used drug and alcohol services

- Almost a third (31.1%) had accessed mental health services

- A quarter had visited an emergency department (24.4%) in the past 6 months

The overall prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was 87.8%, but with a low sample size this figure needs to be interpreted cautiously

Mental health conditions were significantly associated with mental health service use:

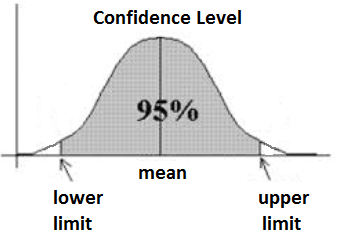

- Mood disorders (Odds Ratio (OR) 5.21, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.64 to 16.58)

- Psychosis (OR 10.0, CI 1.58 to 94.58)

- Suicide risk (OR 6.25, CI 1.82 to 21.43)

Emergency department use was predicted by:

- Mood disorders (OR 5.19, CI 1.68 to 16.0)

- Psychosis (OR 7.33, CI 1.24 to 43.29)

- Anxiety disorder (OR 2.88, CI 1.04 to 7.97)

- High-suicide risk (OR 3.42, CI 1.86 to 13.67)

- Comorbidity (OR 1.41, CI 1.05 to 1.90)

GP service use was predicted by:

- PTSD (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.08 to 7.25)

- Suicide risk (OR 4.57, 95% CI 1.60 to 13.06)

Increased drug and alcohol service use at follow-up was associated with:

- Substance dependence (OR 13.60, 95% CI 1.62 to 114.12)

- Psychosis (OR 13.0, 95% CI 2.14 to 78.87)

Wide confidence intervals were produced by low incidence of some conditions and low levels of access to some forms of services

Discussion, limitations and clinical implications

This is the first study to examine the links between psychiatric disorder and service use in young people with experiences of homelessness, over time. The prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the sample was extremely high, much higher than that reported for this age group in the general population and is clearly indicative of the need for appropriate mental health services.

However, despite 87.8% of the sample meeting diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric condition, only 31.1% had accessed any form of mental health service. In addition, complex needs involving comorbidity and addiction (even if not meeting clinical thresholds) created barriers to accessing care. For many, the symptoms of individual conditions did not meet diagnostic criteria but the combined effects of low-level conditions were no less debilitating.

None of the participants were accessing Child and Adolescent Mental Health services, despite more than 50% being under the age of 18. Many of the participants were unable to access child and adolescent mental health services because they were not in full-time education, a fact which highlights a shocking gap in service provision disproportionately more likely to affect young homeless people.

The authors acknowledge certain limitations with the study, including generalisability to both other ethnic groups and other ‘types’ of homeless young people (e.g. those sleeping rough). Wide confidence intervals were produced by low incidence of some conditions and low levels of access to some forms of services. Self-report may also have been problematic; research on agreement between young homeless people and case managers on contact with services indicates low levels of agreement for certain forms of service use.

This study highlights just how difficult it is for socially excluded young people to negotiate an already complicated mental healthcare system. The barriers to care are often arbitrary, exclusive and, most importantly, unfair.

Barriers to mental health services need to be broken down if we are to help homeless young people

Links

Hodgson K, Shelton KH, Van Den Bree MB. (2014) Mental health problems in young people with experiences of homelessness and the relationship with health service use: a follow-up study. Evidence-Based Mental Health 2014 Jul 3. pii: ebmental-2014-101810. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2014-101810 [PubMed abstract]

Anderson I, Thomson S. More priority needed: The impact of legislative change on young homeless people’s access to housing and support (PDF). Shelter, 2005.

Llamau – http://www.llamau.org.uk/